Some four thousand years ago, Babylonian culture celebrated the new year at the beginning of spring in our contemporary month of March. Since that time, various societies have based their year on the movement of both the moon and the sun. Europe (along with those countries who trace their roots to European origins) eventually adopted the Roman Gregorian calendar. In this calendar, January is the first month of the year which means January 1 is New Year’s Day. In ancient Rome it was customary to inaugurate new consulships on this date. Since late medieval times, it is still customary in some places to observe New Years Day with family gatherings and the exchanging of gifts.

In the Western Christian Church, the liturgical year is based on the Festivals of Easter and Christmas. Easter connects the Christian calendar with Passover and the Jewish liturgical calendar, and Christmas, set on December 25 in the fourth-century Roman calendar, coincides with the (then) pagan observance of the winter solstice. The Church in the West set aside a period prior to Christmas, including four Sundays, as the Season of Advent, and designated the First Sunday of Advent as the beginning of the Church year.

What does this cyclical nature of time mean in our lives? From ancient times, it was useful to be able to designate the passage of time and the cycles of sowing, growth, and harvest in a meaningful way. In several of these ancient societies (in the northern hemisphere), the new year began with the coming of spring and the new growing season. In that agrarian context, there was a strong sense of “life beginning again” and, hopefully, looking forward to the fruitful end of an abundant harvest. Even now, with the New Year happening in the middle of winter (in the northern hemisphere), there is a strong sense of opportunity for renewal and the chance to make changes at the beginning of a New Year. Along with celebrations involving too much food and drink, many of us take time to reflect on the past year and plan for changes we want to make—commonly called New Year’s Resolutions. These are often aimed at some type of personal self-improvement, whether it be physical, psychological, or spiritual.

The same annual cycle plays out in the Church year from the First Sunday of Advent to the celebration of the Reign of Christ on the last Sunday of that year. The seasons that make up that year follow from preparing to celebrate Christ’s birth and eventual return (Advent and Christmas); realizing the divine significance of Jesus of Nazareth (Epiphany); relating to his challenge to, sacrifice for, and victory over the brokenness of humanity and creation (Lent and Easter); coming under the empowerment of the risen Christ (Easter and Pentecost); and learning to live in God’s Kingdom (the remaining period of the Church Year called Ordinary time).

Of course, many of us participate meaningfully in both of these cycles. How do we engage them? What are our expectations? Do the cycles overlap or influence each other in some way? I believe that the greatest overlap of the two cycles takes place in the celebration of Christmas. In contemporary Canadian culture, many people who have little or no connection to Christianity still observe some kind of preparatory period leading up to Christmas. While it’s true that for many of us the secular lead-up to Christmas begins too early (immediately following Hallowe’en) there still is a common sense of preparing for some joyous event that will hopefully bring out the best in us.

I believe that in secular society there is some sense of Christmas being the final commemorative act of the year before celebrating New Years as the beginning of a new life cycle. It is often a time of stating intentions for changes in personal lives. People make plans for the coming year that might involve vacation trips, seeking different employment, or furthering their education. Sadly, if the drop-off in participation at fitness and physical recreation facilities during later January and February is any indication, many people quickly abandon their good intentions and pick up much of the activity (or lack thereof) from the previous year.

Advent is the first season of the Christian New Year. We celebrate this season with provocative Scripture readings and sermons, intentional liturgical actions (lighting of the Advent Wreath and pageants for all ages), and beautiful, ornate worship services at Christmas. As a liturgical leader, I have tried to sustain some of this Advent spirit into the season of Epiphany (in January). But the experience of a “bleak mid-winter,” the lack of cause for celebration in other areas of peoples’ lives, and drop-off of Sunday attendance following Christmas can quench this spirit of “new year enthusiasm.” Sometimes, the Advent energy may be recaptured with a well-planned and participatory Annual General Meeting. This congregational gathering, typically held in February, can capture similar imaginations and energies found in the personal plans we make for the secular New Year.

So, does engagement with the “new year” (secular and church) provide an opportunity to re-start? Is it a resource for renewal? The short answer is: it can be! But in both the secular society and the church congregation, it is not enough for an individual to try and re-start or renew on their own. In both arenas, it requires a community. Re-starting requires companions who are equally committed to following through on good intentions and determined to consciously engage the cyclical nature of their lives. It requires support for one another—whether on a new physical fitness regime, or a commitment to grow as a disciple of Jesus Christ through being immersed in Christian learning and action. Together with others, both new years can be effective springboards for transformation.

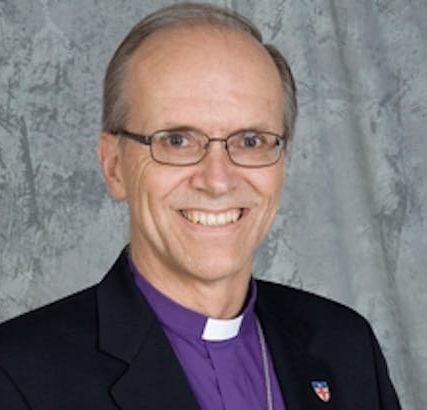

Don Phillips is the former Bishop of the Diocese of Rupert’s Land.

Don Phillips is the former Bishop of the Diocese of Rupert’s Land.